The Horn of Cape

The exhibition aims to, after a long time apart, once again bring together three artistic positions that, at numerous group and solo exhibitions in the 1990s, inspired new ways of interpreting the visual nature of the present day. In the work of Veronika Bromová, Markéta Othová and Kateřina Vincourová, conflicting reflections of an uncertain identity and a hidden, obscured and mediated reality gave rise to a clearly defined stylistic quality characterised by a tense romantic-classical dichotomy (expression – order, performance – meditation, image – object) and spanning multiple artistic media and forms. The effect of their presentations, which can be summarised by the slogan ‘tension gives way to release’, was to give shape to and simultaneously ironically comment on a newly glimpsed, emancipated space-time with all its possibilities, limitations, confrontations and intersections. The three aforementioned artists regularly explored one of these aspects through the implicit conversations between their exhibitions and through the solutions proffered in response to their shared challenges. The exhibition at GASK attempts to confront three stylistic starting points (represented by a selection of works from the 1990s) at the midpoint of the artists’ journeys and to test their current contemporary possibilities (in the form of their more recent works).

We live in a digital age in which the image of the world is of a technical nature. This state of things is reflected in a consciousness that is unwittingly shaped by calculating apparatuses. As convincingly outlined by Vilém Flusser, we have been aware of its hegemony for more than thirty years, and we are only slowly becoming aware of the effects of the tools that define our practice and make our desires come true: ‘Tools have three functions: (1) to produce something, (2) through this, to change our surroundings and (3) to change the people who use them. The first function is the intended one; the second and third are unintended consequences of the first. The first can be called economic, the second ecological and the third anthropological. Only recently, people have begun to take the ecological function into account when designing tools. The anthropological function, however, is not considered, so that the tool’s repercussion on man and society is not only unintended but also unforeseen, and this explains why history is filled with such surprising (and sometimes catastrophic) events. […] Today, the repercussion of tools is even more apparent than it was then: young people dance like robots, clerks at bank counters behave like automatons, scientists think like computers, artists like plotters. At the same time, the design of tools is increasingly more conscious and, as they become softer (e.g., soft-ware), more comfortable as well.’ The affirmative artistic response to the rise of technological (computer) imagery in the late 20th century was essentially twofold: identification and naïve acceptance on the one hand, and an ironic caution on the other that forged its own path (or, more precisely, took a detour) towards the ‘mediatic’ nature of reality. It was a path characterised above all by misleading or manipulative techniques, subtle shifts in meaning, a reliance on the innate capacity of seeing as (unprejudiced) seeing, and the critical premise that ‘appearances are deceptive’.

The question remains: what has become of these visual presuppositions, how have they evolved and what is their current potential? And what repercussion do our tools have on the origins of seeing, which is intentional in nature – in other words, what is their effect on the imagination?

The exhibition’s three parts, brought together by subtle semiotic relationships and small mutual interventions, present a creative conversation among three experiments, three explorers of a concrete vision that defies incorporation into computer algorithms and their perfect visual output. The vibrant nature of this interaction has encouraged those characteristics of their diverse artistic expression capable of supporting one another and enriching each other with new meaning. In this juxtaposition of three new artistic positions with three visual memories of the time when digital images of our world were first emerging, one can glimpse the Horn of Cape: a maritime metaphor for a risky, unsteady voyage, a childishly nonsensical utopia of a world in which we can still be at home. It is a voyage we must undertake by ourselves; it cannot be entrusted to software or artificial intelligence, because only for us does it have any meaning.

Veronika Šrek Bromová

was born in Prague in 1966 and studied graphics and illustration under Professor Jiří Šalamoun at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, from which she graduated in 1993. She was a finalist for the Jindřich Chalupecký Award in 1997 and 2000. In 1998, she received a fellowship to the International Studio Program in New York. Her work has been well received abroad, and in 1999 she was the first Czech female artist to participate in the Venice Biennale of Contemporary Art, where she presented the environmental installation Earthzoo. In 2003, she was awarded a three-month fellowship from Kunsthalle Krems/Factory. After heading the New Media Studio (Photographic and Digital Image) at Prague’s Academy of Fine Arts in 2002–2011, she spent several years teaching at the summer programmes of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Since 2015, she has taught in the Cross Media Art Studio at the Anglo-American University in Prague. She applies elements of art therapy and ‘artephiletics’ (a reflective, experiential approach to art education) in her art and teaching. In 2011, she founded the Kabinet Chaos gallery, where she organises artistic gatherings, exhibitions, residencies and workshops. She has also contributed to the founding of several performance groups, such as Sirény z Titany (Sirens of Titan), Die Früchte and Creepeedolls.

Bromová’s contributions to the Czech art scene include experimentation with digitally altered photographs, ‘un-painted paintings’ and provocative ‘self-performances’ in which she touches on gender themes. More recently, she has shifted her focus onto archetypes and rituals in juxtaposition with contemporary pop cultural modernity. She works in a wide range of media, ranging from photography, video and installations all the way to objects, paintings and drawings, creating works that are of a distinctly performative, theatrical character.

Markéta Othová

was born in 1968 in Brno and attended the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, where she initially studied film and television graphics before going on to graduate from Professor Jiří Šalamoun’s Studio of Graphics and Illustration in 1993. The following year, she was awarded a fellowship from the French Institute for a three-month study exchange in Paris. A three-time nominee for the Jindřich Chalupecký Award, she won the award in 2002 and did a month-long residency in New York that year. She received the Michal Ranný Award in 2020.

A large part of her work consists of photographs in which she captures the visual signs of an intimate experience of time. After initially working mainly with large-format black-and-white photographs (Utopia), she later switched to colour and relaxed her previously strict and conceptual focus on one particular image size. In her experiments with the serial photographic form, she uses the tension between a unique visual event and its sterotypical image model to create ‘picture poems’ that explore the relationship between things and their visual representation in a new, ironic and non-illusionistic spatiotemporal constellation.

She also does graphic design for books on art, photography and architecture and produces graphic and architectural designs for exhibitions.

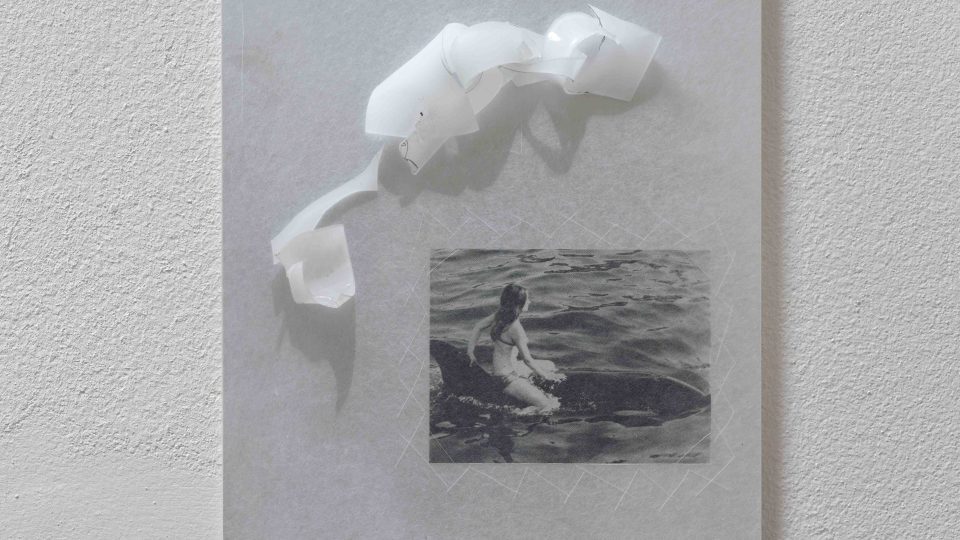

Kateřina Vincourová

was born in 1968 in Prague. She attended the V. I. Surikov Academy Art Institute in Moscow in 1986–1988 and subsequently (1988–1994) studied under professors Ladislav Čepelák, Miloš Šejn and Milan Knížák at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. She was awarded the Alexander Dorner Prize in Hanover in 1993, and in 1996 she became the first woman to win the Jindřich Chalupecký Award, which came with a residency at the Headlands Center for the Arts in California (1998). In 1999, she received a year-long DAAD residency in Berlin.

In her art, whoch consists primarily of installations and objects, she explores the potential of space – interior and exterior, the ambiguity between inner and outer, between stability and instability. In the 1990s, she began to incorporate unstable non-sculptural materials such as plastic bags, foam rubber and other synthetic substances into her monumental installations and objects (View of Captain Nemo’s Chamber). Her work tends towards allegory: the narratives of her installations reference society-wide issues, while her ‘spatial drawings’ usually explore intimate emotional experiences. Her site-specific spatial arrangements establish new rules in a game involving intimately familiar everyday signs.